That time in 2003 when I hung out with Sufjan Stevens in Oslo, Norway and wrote a bad story afterwards

A story about a story, which is a weird preface (with its own little preface) to Things To Come

Preface: I suppose my few posts so far might look like the ravings of someone mentally unhealthy (trying to avoid the ableist ‘madman’). And I’d be the last to deny that possibility. But even the mentally and/or emotionally unwell have something legitimate, and even coherent, to say. I sincerely (if provisionally) believe that if these fragments are ever gathered and read as a continuum, a larger picture will emerge. I am actually saying something here. And I have begun to suspect that it is a sort of on-the-ground report from within the Capitalocene or Anthropocene (from someone fighting bareknuckled and bleary-eyed to be a tiny glowworm glimmer of the Chthulucene we have always been). More plainly: I am a poor man trying to report on his poverty, material and spiritual, from within the collective poverty, material and spiritual. In the future we may rely on such crackpot reportage, when we all live in the cracks. Admittedly, it is a fairly phantasmagorical report. Yet, as I have argued in previous posts, that is exactly the authentic feel of this moment. Dream is verisimilitude. If you read on, then, the extended trip through a shifting metaphor will take you somewhere concrete. (And once you know the second half of that metaphor, you will no doubt find the word ‘concrete’ ominous.) But first that shifty metaphor is deferred for a story about a story:

That Time I Hung Out with Sufjan Stevens and He Made Me Feel So Bad I Had to Write a Bad Story

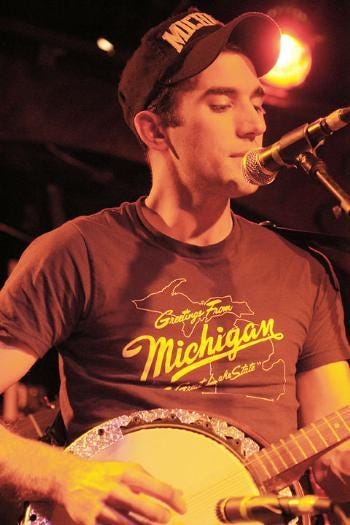

My very first work of fiction to be published, circa 2003, was called ‘The Man Whose Role it Was to Travel Far and Wide to Every Location of Beauty and Wonder in Order to Stand in its Midst and Be a Piece of Crap’. Not too long ago, I re-read this little downtrodden wonder tale and found that it was not nearly as bad as I had recalled. (I have a little more mercy on the young man who wrote it these days.) I wrote it on an airplane in the summer of 2003. I was on my way back to Glasgow from Oslo where I had spent a day pottering about the Norwegian capital with Sufjan Stevens. Yep, that happened. I had no idea who he was at the time. We explored Oslo, took a ferry ride to an island, and discussed writing fiction. (There are other amusing details to this story. Maybe I’ll tell them sometime.) We had both been on a panel at a Norwegian christian rock festival the night before and, rather inexplicably, I had been scheduled to speak after Sufjan’s set at around 2 am in the morning. It was my first, woefully inadequate attempt to say something about a ‘theology of monsters’. I didn’t try again for over a decade and when I did it amounted to an hour-long hesitation to directly address the topic. Listening again, that ‘keynote speech’ is also not as bad as I recalled, helped not a little by bizarre imagery from Guillermo del Toro and R. A. Lafferty. (I’m more merciful these days to this comparatively young man as well, though I now have many theological questions for him. I’m just glad he was able to finally break free from the christian cult, though his brain is admittedly still porous to its caressing tentacles.)

Sufjan and I were housed at the same place and we had time to kill before our respective flights home. He was genuinely one of the nicest people I’ve ever met. Even without knowing who he was, the story I subsequently wrote shows I felt shabby next to his musical and lyrical eloquence. (And physical prowess—he was in better shape than me. We had to run to catch the ferry and he had to slow his pace for me to keep up. Then he was winsomely solicitous about my wellbeing as I tried to catch my breath on the boat. Told you he was a nice guy.)

The weird little tale I wrote back then describes a character who has ‘word-warriors’ crowding at his mouth from the inside, as soldiers might have crowded at the belly-hatch of the Trojan Horse in the crucial moment of egress within the walls of Troy (I got this image from an unfinished story by C. S. Lewis). His words are so eager that they congeal in a melee of bodies that can only escape the hatch piecemeal as nonsequitous globs, disjointed and ultimately disarticulate. What the character ends up saying is cringe, but oddly effective for that reason. Maybe too effective.

That is the case with this substack. Every idea formed for a post does not prosper. Every post that actually forms is cringe, but strangely effective for that reason. Timothy Morton suggests we embrace rather than shun the queasiness of kitsch within the Anthropocene: ‘as if I am tasting something familiar yet slightly disgusting’ and ‘I enjoy, a little bit, this disgust’ (Dark Ecology, pp. 123-124). Why would it be important that my works old and new (look on them, ye mighty, and gloat) are a little bit repulsive to their creator as well as their audience? Because, as Morton continues: ‘Beauty is always a little bit weird, a little bit disgusting’ (ibid.). If we’re not flinching a little from our creations, we haven’t made them well. They’re too smooth to provoke significant interaction, much less maker-beholder synergy. They’re bad lies (instead of good lies).

Ah, hell, try reading one whole sentence of the fruitfully obtuse syntax of critical theory:

‘Beauty always has a slightly nauseous taste of the kitsch about it, kitsch being the slightly (or very) disgusting enjoyment-object of the other, disgusting precisely because it is the other’s enjoyment-thing, and thus inexplicable to me’ (Morton, ibid.).

He’s saying that ‘beauty is already a kind of enjoyment that isn’t to do with my ego, and is thus a kind of not-me’ (ibid.). Did I make that art object (the story, the essay, the post, the photograph)? Ew. I don’t like it any better than you do. Yet we both do like it, a little. Because it’s not-us. It’s one more thing articulating obliquely that we’re not alone. Something else exists. That not-me object is giving me the planetary creeps and it’s suddenly pleasurable to be here, part of the mess we’ve made, and a little queasy. That’s what an encounter with beauty feels like. It’s what Donna Haraway calls ‘Staying with the Trouble’.

More Bad Things to Come

All this is to say (and now we finally get to the shifting metaphor): I’ve had plenty of ideas for substack posts, overeager and over-egged word-warriors ready to attack your city from within. (The martial metaphor seems needlessly aggressive, but let’s play it out.) Yet very few have leapt to the assault, not even a handful. A more honest image might be that they do not so much crowd the escape hatch as loiter there one by one and recede, re-approach, hesitate, fall back again, like so many faint-hearted parachuters.

This post is one timidly bold fellow making the leap. He is falling. His heart is in his throat, his limbs are flailing, and his weapons have slipped from his sweaty grasp to drift just out of reach in the screaming air.

As he plummets through acres of empty blue—the initial terror of freefall now swallowed into unmoored calm—he formulates his reasons for not jumping before now. That is, he tells a little story to himself about his indecision. It was not a lack of nerve. He mistakenly told himself this at first. Rather, he and his fellow warrior-jumpers indeed crowded the escape hatch in their meandering way. And he sees now why they hesitate: each one carries in his armored bosom a missive too precious to its recipients to be hurled halfcocked and headlong at the wrong moment, its bearer equipped only with a motheaten parachute or rusted spear. More plainly: his thought is deep, untrivial, bordering on genuine insight. Foreboding shapes stir within him. Serpentine forms can be seen at close range to coil beneath his skin. In his tiny falling body, the medium is the message. The monstrum—the portent, the omen, the revelation—that this warrior-jumper hosts will certainly break his flesh when it finally breaches, but may the quality of its light not fail! Then again, if it squirts out as a pez-dispenser puppet that hurries into the shadows of the ship’s hold, it will certainly return, grown sleek and predacious in its body-suit practical effects. This too is revelation and sometimes we can only be eaten up.

But it’s just possible the monster will emerge from the body of the warrior-jumper as some abstruse energy-field that engulfs its recipients in different ways. Biosemioticians insist, after all, that ‘natural play’ is as evident as ‘natural selection’ in the long tale we call evolution (and others, such as Lynn Margulis and Donna Haraway, call ‘involution’ or ‘sympoiesis’). Will you play with my monsters as they hatch from the soldiers broken by their fall from the belly of a gift horse you should have looked in the mouth?

Look, you already are. If you’ve read this far, you’ve succumbed to the monstro-ludic. I’m delighted you’ve played along. And so are the monsters. Yes, monstrosities can delight, and even love. They are not all sinister, even if they are all perilous.

And yes, this missive is a monstrum. It is, at last, bringing something to light. (‘Showing’ is the prime function of monsters according to some monster theorists—though they shine in a characteristically complicated manner that occludes as much as it discloses). The thing that bursts from this particular word-warrior presages what’s to come: larger (much, much larger) monsters on the horizon, entities the size of islands or deserts whose movements would only be observable by some analogue of time-lapse photography, not unlike the enormity of blooming flowers or wheeling stars. Such mega-leviathans do not emerge from my broken little mind (much less my broken little word-warriors), but I contribute with the (more-than-human) collective to limning their form-defying forms.

To wit: here are some of the topical hoplites that’ll be hopping from the hot hatch of my helenequine (not to say harlequin) brain presently. Romance, eroticism, trees, prayer, religious syncretism, poems, original philosophy (not sure why or how that’s happening but it is), as well as thoughts on academic articles I’ve written recently and the continuation of a phenomenology of precarity through the lens of Lafferty’s story ‘Scorner’s Seat’ (the subject matter of my first three posts).

Your inbox is a Trojan Horse for monsters. Of course it is. Things are creep-leaping out of it to open your gates to the ingress of still more horrors. You’re fated to never be ready for it. So let’s just succumb and traverse the monsterscape together.

More reports to follow.

If I were rewriting this, I might add right at the end of the section titled 'That Time I Hung Out with Sufjan...' and just before 'More Bad Things to Come':

Perhaps Sufjan's performance was so smooth, so exquisite (and it was) that my shitty talk was its necessary, compensatory pendant. And my subsequent crappy story was the world injecting some crunchiness back into things to keep the balance. The set was intimate, a small room with a small crowd, Sufjan with an acoustic guitar, accompanied by only one other player, another very nice chap called Emil (who booked me for the event) who delicately played an electric guitar in the creamiest, carameliest way I've ever heard that instrument played. Sufjan's vocals were one of the wonders of the world, honestly, and I'm not even particularly into that kind of thing. But I was six feet away watching him manipulate breath, microphone, sonority, and acoustics like I've never really encountered elsewhere. I even asked him how he did it the next day. He paused thoughtfully, smiled (almost to himself), and simply said: 'Well, I have to keep some of my secrets.' He too knew the value of preserving mystery. I don't begrudge him his basically perfect performance. It was amazing and there is a place for this. But some of us have to be the dirty-furred primates throwing a little shit afterwards.

[With this paragraph in place, the subtitle 'More Bad Things to Come' takes on further significance.]

I also forgot to mention that I was vocal about my disappointment with my talk the next day and Sufjan was very sincerely insistent that I was being too hard on myself and that there was worth and insight in what I had tried to articulate.

Nice. Guy.