My Story with Philosophy So Far (A Sketch)—Ch. 1: Origin Story

Tracing my intellectual journey (with apologies for how wanky that sounds) from childhood up.

So why do I call myself a philosopher? Do I fancy myself so juicy? So electric?

Opening Epigraphy:

The following concatenation tells the tale in antiphony:

‘In the nights in their thousands to dream the dreams of a child’s imaginings, worlds rich or fearful such as might offer themselves but never the one to be.’ (Cormac McCarthy)

‘Human experience, combined with the power of the imagination and understanding, can break down all barriers, enabling a person truly to understand that thing called fate at work in his life—not unlike the experience of simultaneously seeing one’s reflection in two different mirrors.’ (Yu Hua)

‘It says of him that he represented feeling with enthusiasm; a reference like that makes fun of both feeling and enthusiasm, whose secret is precisely that they cannot be reported at second-hand.’ (Kierkegaard)

‘People’s endowment of the numinous is not restricted to insider or outsider.’ (Yan Zhitui)

‘Off we go again. But before we do, we’ll make ourselves as little as can be. What should be elucidated, in the final analysis, is indeed this: ultra-metaphysical thought is coming to grips with the little.’ (Catherine Malabou)

Preface:

I don’t expect too many people, if any, to be interested in my biographical details (intellectual or otherwise). I write this to try to clarify some things for myself. I make it public as an experiment. If anyone reads it, I want to see if it might create resonances and/or responses from others and their own peregrinations. Thus, feel free to comment and make it a dialogue rather than a monologue. It is not really, of course, the latter, but rather a dialogue with myself. Feel free to join our chat. Sketch your own journey if you’d like, here or elsewhere. And thanks for reading.

Ch. 1: Origin Story

I’m just going to come out and say it plainly. I was born a philosopher. It’s not a boast. I can’t help it. I do have huge reservations about stating this so baldly, which I’ll mention below. I suppose in this sketch I’m trying out the claim, testing it a little.

Before getting to some of the formative fact(or)s, let me say a word to clear the ground conceptually. (If you have no interest in that, skip to the next paragraph.) I used to say that we all do philosophy and thus in some limited sense we’re all philosophers. Nowadays I’m not entirely sure that’s accurate. We do all adopt the philosophies we’re born into and operate on those assumptions. But I’m not sure absolutely every one of us thinks through them to significant degrees. (To paraphrase the Zhuangzi: can anything keep the wanderers from wandering, and can anything set un-wanderers to wandering?) Now those who do (consciously wander/wonder) may not be philosophers per se, but they are certainly doing philosophy, be they a breastfeeding mum or a bicycling athlete who never so much as crack a philosophy book or hear one term of conceptual jargon. But I’ll here reserve ‘philosopher’ for something a little more specific: one who intentionally, self-consciously, and continuously thinks through, at great length and with rigour, various taken-for-granted concepts and assumptions that arrange our mental worlds and our cultures. It is in that sense that I just seem to be bent or wired for the disposition and work of a philosopher (or a philosopher-adjacent thinker). As some seem wired for visual art or the sciences or acting or politics or what have you. (Eventually I’ll have to interrogate my repeated use of this term ‘wired’.) And as some wiseacres out there are wired for two or more of these (the over-endowed bastards), even this stricter sense of ‘philosopher’ may apply to those who never hold the official position of philosopher. I think that, for example, various authors of fiction are literary philosophers. Mary Shelley, Franz Kafka, Jorge Luis Borges, Flannery O’Connor, N. Scott Momaday, Toni Morrison, Chinua Achebe, Ursula Le Guin, Yukio Mishima, Leslie Marmon Silko, Cormac McCarthy, Yu Hua—you could make a very long list. (And yes, of course, I think my special interest, R. A. Lafferty, fits squarely on such a list.) Even some canonised philosophers were likely literary artists playing at being (very good!) philosophers. (The prime examples being Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. The latter self-described as such.) The list of literary philosophers extends as far back as humans go and into every cranny and culture of the globe (including those allegedly not ‘literate’, for literacy and ‘texts’ are larger than our western circumscriptions of them—see Christopher Teuton’s Deep Waters: The Textual Continuum in American Indian Literature). I leave it to you to think of philosophers who might abide in otherfields, the arts or otherwise.

So, with this qualification stated, let’s move on.

I don’t know the age I first started hearing it, but somewhere in my pre-teens my dad started to say two things of me in his playful, soulful, tenor voice (which always struck me as akin to that of an enthusiastic DJ for a blues and/or jazz radio show), verging on baritone when he declaimed: ‘My son, the philosopher’ and ‘My son, the scholar’. I was both young enough and of ‘low’ enough cultural milieu to recognise these words as words but have no real idea what they meant. My dad was a southern baptist pastor of a small working class congregation in Indianapolis, Indiana. (Admittedly he was a rather unusual variety of the species: a long-haired, bearded, and tattooed pastor who wore a leather vest, a large metal cross medallion, and who played electric piano in rock bands. Any new friends of mine initially thought he was a biker. This was in the 80s.) He was from a working class background in Arizona, estranged from his parents as a kid but adopted by a kindly older couple. Through conversion to christianity (his ‘cure’ for alcoholism—to be facetiously reductive) he became intellectually awakened, particularly during theological training at seminary. Karl Barth was his favourite theologian and he never tired of giving me a quick sketch of how neo-orthodoxy grew out of liberal theology, as if he’d never mentioned it before. For no clear reason I can think of, I liked to pull his little volumes of Greek grammar down from his wall-sized bookshelf in his church office and copy down the Greek letters and words, not really learning their meaning, just enjoying the act. This, I suspect, is why he called me a ‘scholar’. A scholarly pursuit of languages never panned out for me. Other aspects of scholarship would only come much later and be applied perhaps mostly to literature (though, as I’ll outline in a moment, I never became much of a dogged scholar, PhD in English Lit notwithstanding).

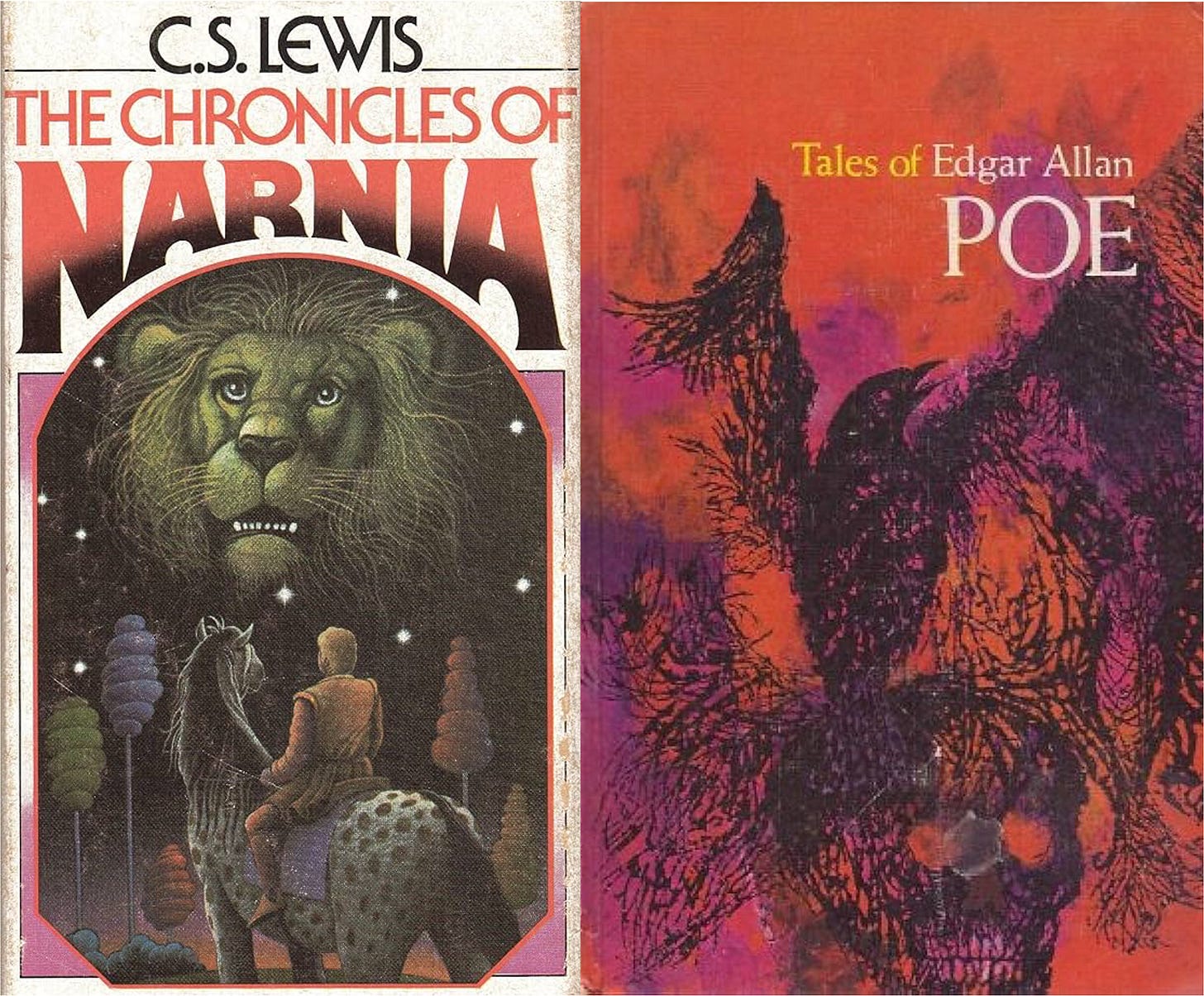

Why did he call me a wee philosopher though? Here’s where I have to start talking about C. S. Lewis. I first read ol’ Clive Staples in second grade, around 6 or 7 years old I guess. (The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, as you’d guess—and so began my incurable (ab)use of parenthetical statements.) I’m a little amused now to realise that I spent my twenties being vocal about my love of CSL, then my thirties being distracted by various other thinkers and writers, and my forties being embarrassed of my youthful passion for Lewis. Very, very recently I have been creeping back toward little glances at the old fellow and am finding I may be able to salvage a thing or two from this undeniably gifted author who co-formed my mind before I even knew such things occurred. (The other co-former was Edgar Allan Poe of all people. I must apologise to both men for making them odd bedfellows in my burgeoning weird imagination. These two authors loom over my pre-teen years. When I set pen to paper in my late teens I sounded like what you’d expect: an early 90s midwestern working class kid unconsciously aping a mid-20th century Oxbridge don and a 19th century Virginian misfit Goth. It wasn’t too good. And oh how their influence lingers.)

Was this more gruesome tableaux complementary to wardrobes and framed paintings that led to alternate realms, accessing instead tenebrous underworlds through grotesqueries? Is epistolary diabolism a clue to the linkage?

I had no idea that Narnia was inducting me into hardcore philosophy. I’m sure many have read those books and had no more than a brush with philosophy rather than an induction. That brush is inescapable, however, even for the most casual reader. The idea of accessing other worlds through mundane portals is probably the biggest conceptual speculation of my childhood (and its implications for modalities, possibilia, meta-dimensionality, and multiverse). And somehow my dad clocked how deep it went for me and dubbed me the filial philosopher. I say ‘somehow’, but he himself set it in motion, having given me The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe to read while I was home sick from school with a fever for two days. When I was finished he addressed me from his favourite reading chair as I stood before him, presumably at eyesight in my smallness, and queried: ‘Who do you think Aslan represents? How so?’ A little catechism in christian allegory. Doesn’t sound like much, I know, but to be initiated into such thinking, simple as it is, at such an age, and in the afterglow of the first literarily magical moment of my life, well, it leaves a mark.

I’m sure his impression about me was helped by my also reading Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters before I even turned twelve. I hardly understood a word of it, but my enthusiasm for it was immediate and abiding. The thought of demons writing letters of advice on damning souls with sardonic wit (reminding me somehow of Monty Python, which I was also drawn to without really getting) horrified and amused me in equal measure. (Putting the invented word ‘screwtape’ in a book title is also one of the great proto-punk moves of 20th century English Lit.) Various things about metaphysics and ethics were happening within my adolescent mind through Lewis (for better and worse). Thus, when I read his books Mere Christianity and Miracles after high school graduation at age eighteen, sitting in the family mobile home during one of Indiana’s perma-humid summers, I was primed to be hooked (on philosophy). Particularly the latter book’s sustained ‘argument from reason’ for the existence of god (or the defeat of naturalism) put me through my first paces. What shocked and delighted me though—the real takeaway from Miracles—was that Lewis there propounded the view that all those parallel universes he fantasised in Narnia were based on his sincere, rational belief in the existence of actual other worlds or alternate realities. You maybe can’t imagine what that’s like, to discover a semi-private fantasy life suddenly promulgated as reality (or part of reality, contiguous with the known). It’s one of those moments you look up from a book and the world has changed around you.

(And while Lewis had furnished everyday portals to otherworlds, Poe had kept pace with an alternate landscape of the macabre: cats in walls, people tortured or axe-murdered, corpses rising from their coffins. Was this more gruesome tableaux complementary to wardrobes and framed paintings leading to alternate realms, accessing instead tenebrous underworlds through grotesqueries? Is epistolary diabolism a clue to the linkage? That’s a discussion for another chapter.)

Unfortunately, this particular induction into philosophy gave me no tools to critique the religion I was brought up in, nor my socio-economic circumstances. I suppose it’s no wonder my mind joyously fled to the possibility of otherworlds. (Though I do not believe deprivations to be the only causes of Sehnsucht.) Indeed, my sense of wonder might be my strongest impulse and it is this very thing that kept me so long from seeing the beauty and mystery of Marxist or otherwise ‘left-wing’ (or anarchist) thought and praxis. Some blame, however, may also be laid at the door of the left who do not always exhibit wonder or mystery in their ethos and aesthetics. Sometimes they exhibit active distrust of such things (‘Beware the opiates!’ they cry). As a result, though I have self-described as ethically left-wing for some years, these vectors of thought have finally captured my imagination only very recently. It is in no small part through the podcast Death // Sentence that I have entered this new world. Their delightfully nerdy, down to earth, yet heady discussions of genuinely good science fiction & fantasy, heavy metal, and left-wing philosophies, from an often hilarious yet heartfelt, humble, and compassionate disposition, is perhaps my second induction into philosophy, late in life. I am at long last reading continental philosophers with gusto! But this too is a story for another chapter. I will add here, however, that some sincere and serious engagement with the ‘otherworldly’ may be just the shot in the arm that leftist thought needs. Anathema as that might seem to a materialist philosophy. (It can’t be helped. As someone who came, as we’ll see, to the intellectual—and later, academic—life from way outside its centres, I am continually letting slip shibboleths.)

So it was at the age of eighteen that I first became self-aware that I was a philosopher. I still didn’t self-identify that way but I knew I was doing that work without calling it such. (I even made my first sketches of philosophical reasoning in a since lost notebook of the time.) From then on I just couldn’t stop thinking about how we know things and what the nature of reality was, and I wouldn’t even know the terms epistemology and ontology for a few more years. I can literally remember washing dishes with the handheld sprayer at Taco Bell and formulating reasons for why I was convinced our minds were in some sense immaterial (or super-material). (I’m currently getting back, at long last, to philosophy of mind and consciousness—the state of play is utterly fascinating.) And I repeat: I couldn’t help it! I remember clocking that I was doing this internally from time to time and wondering what the hell was happening. I really did!

All throughout my schooling I had been a very poor student (academically—but yes, financially as well, free school lunches all the way), so I decided to defer going to college, which I could only have gone to on a not-likely-to-be-obtained scholarship in any case. I’ve never been a very practical thinker, so I naively put this down to my own choice and nothing more. I’m kind of glad that lad didn’t have his heart set on something that would’ve proven inaccessible to him. He chose to form a punk rock band and get married and start raising babies at a very young age instead. (This is yet another story for another time.)

And in early fatherhood he finally discovered philosophy books proper. Mostly various intros to philosophy and its major branches, but also Walker Percy’s existentialist and experimental Lost in the Cosmos, on C. S. Peirce's semiotics (another C.S.!), along with a few other things I can’t recall. A neighbour, who was studying philosophy at IUPUI (Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis), wisely admonished me to beat a path straight to Plato and Aristotle to get grounded. It would still be a few years before I took up that advice. In the meantime, my voracious literary reading included the likes of G. K. Chesterton, George MacDonald, Charles Williams, Flannery O’Connor, and Walker Percy—theologically bent novelists all and thus seemingly not a million miles away from Lewis. But through MacDonald I was getting a more liberal Romanticism; through O’Connor, Teilhardian notes; through Percy, a Kierkegaardian orientation; through Williams, beautifully batshit esotericism; and through all, a stronger dose of sacramental ontology. An odd Oklahoman named Raphael Aloysius Lafferty would soon eclipse them all and prove over the years to be one of the most inspiring and maddening authors I’ve known. His deeply conservative impulses colliding with his profoundly generous impulses and wild sense of wonder combine for a thorny yet thrilling reading experience.

Fast-forward.

Finally, by my early forties, thanks to free undergrad education in Scotland, I completed a joint honours (double major) bachelor’s degree in English Literature and Philosophy, ‘first class’ (summa cum laude). I point out that it was first class because it’s just such a shock that the kid who literally slept through as many classes as he could in high school (working weeknights) and barely graduated by the skin of his teeth, and who then deferred further education for several decades, was able to become that passionate and accomplished of a university student. It wasn’t easy. I had to constantly trick myself to meet deadlines. And there was a fair bundle of childcare ongoing throughout (including post-grad). But the intellectual pleasures fuelled and propelled me. My not free, but affordable PhD was then crowdfunded by generous people I’ve known over the years (many of them, to whom I am thankful, from what I am now calling my religious cult days—a topic I will try to write about as soon as I feel ready and able). This too was not easy, yet was fuelled by passion and joy in the endeavour, having chosen the exact topic I really wanted to do: an ‘ecomonstrous’ reading of Lafferty and Cormac McCarthy. I passed my viva (defense) in August of 2020 with ‘no corrections’. (I cannot tell you my surprise—and then relief!) It has not proved financially remunerative thus far, but nothing less than researching and writing about my true passions and obsessions could have gotten me through that ordeal and across the finish line.

Burnout and some recovery years inevitably followed, abetted by personal crises and upheavals. I will discuss these elsewhen. For now, to conclude this first sketch of a first ‘chapter’ of this account of an intellectual journey, I come to the reservation I stated at the outset. Having done my PhD in English Literature, why would I call myself a philosopher and not simply a literary critic? Well, remember when I said I never really became much of a scholar? I do have a scholarly impulse. I do like to trace things back as far as I can and trace them out as wide as I can. I’m forever falling down the infinite regress of reading so and so to understand so and so who influenced so and so, and so on. Comparing this school with its foil in that school and a tertium quid in yet another school. Folding in this burgeoning discipline along with that forgotten discourse. Ad infinitum, ad delectatum. So yes, I have a scholarly impulse and I’m capable of doing the necessary scholarly work for a given research project. I am indeed a researcher. Yet I consider myself first and foremost a reader, rather than a scholar or even a literary critic.

The Critic is an old school ontologist of sorts, carving literature at the joints, offering up choice cuts in soaking pink parcels. I do enjoy such delicate butchery. But by impulse and disposition, I’m perhaps more of a paraclete with literature, calling out from beside it, advocating for it.

Reading is the one true talent I have. I had no idea it was an actual talent, all growing up and for most of my adult life. I eventually understood I had a certain capacity of intelligence to be so voracious for it, but I didn’t understand that being able to read (not merely to be literate, but to parse, to perceive and interpret, literature—and film, etc.—beyond a surface level) is not something everyone has, and that, to be frank, I have to an exceptional degree. (Even if I’m clunky as hell about it most of the time.) This was honestly news to me midway through my life.

I’m comfortable calling myself a Reader. Even a gifted Reader. The literary critic part is like the scholarship. Something I’m capable of doing and happy to do as part of the work. I make this distinction between Critic and Reader because the former is more formal and the latter is more lateral. The Critic is an old school ontologist of sorts, carving literature at the joints, offering up choice cuts in soaking pink parcels. I do enjoy such delicate butchery. But by impulse and disposition, I’m perhaps more of a paraclete with literature, calling out from beside it, advocating for it, enthusing about it, by showing as best I can (and not even always my best!) how it coruscates and quivers, and delivers all the material transformations it performs by its dark-bright arts. (Oh, have I not mentioned that I’ve never stopped being fascinated by theology?)

Still, a Reader who is also a philosopher? I did include philosophy as a key component in my doctoral thesis, which continues to influence my academic work. The main school of philosophy I engaged at the time was Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), with nods toward its frenemy New Materialism. Whilst continuing research in those areas I have been branching backward into other (unbeknownst) frenemies, Nietzsche and Kierkegaard, as well as the more recent past of Jaques Lacan (with hopes of reading his double too, Levinas) and sideways into Alain Badiou, Francois Laruelle, and Slavoj Zizek. And many, many more. Whitehead and Wittgenstein are calling. Spinoza (who I wanted to ignore as I’m not much of a monist) won’t leave me alone either. And I continue to pointedly delve into counterpoints and overlaps from the philosophies of non-Eurocentric cultures (currently Native American and Chinese). But all this is still research, the scholar’s work. Indeed, I recently heard a philosopher make a distinction between a professional scholar of philosophy (often called a philosopher), who focuses on the history and explication of philosophy, and a philosopher proper, who launches out into the construction of new interrogations and/or systems of thought. For anyone who’s read in the field, it’s very easy to spot the difference. I value very highly the scholarship of philosophy and rely on it perpetually. But the juice, the electric current, is in the philosophers, those performing the original work, then and now.

So why do I call myself a philosopher? Do I fancy myself so juicy? So electric?

In a (hazel)nutshell (recalling the cosmic image from Julian of Norwich): I have found that I do, and I simply must do, the latter (the work of the philosopher proper as opposed to the scholar of philosophy). I simply cannot find all that I need already out there in the philosophers (and anticipate I never will, no matter the research). I perforce philosophise. I will continue to arrange and combine, which is its own kind of original philosophising, but the arranger must justify the assemblage through their own hand-crafted ligature. And I will probably have to make some of my own limbs and beams and buttresses, and pastes and joints—as well as, conversely, widen some holes and rip some new ones. (Even in my literary criticism, I am doing philosophy. My last three academic essays are building towards provisional systems of thought. Or better, improvisational structures of feeling. These piggyback strongly, and meaningfully, on already existing philosophical structures—Lacanian, Marxist, Thomist, Cherokee, whatever—but in new agglomerations with new DIY additions and protuberances made from a host of sources, philosophical and otherwise.)

But such bespoke decollage-collage is not the only impulse behind my self-understanding as a philosopher. It really goes back to that primordial and formative sense of wonder. My lodestone. I have things to do and say for my while on this planet yet. One of them is to explore and report on the ontic warp and weft. Firsthand. I simply must. It is in me as a pulsing ember seeking, if not its source, its souciance (that is to say, solicitude—care and, wish of wishes, being cared for, with ‘being’ hefting all its metaphysical weight; some have called it ‘donation’ or ‘favour’, on the ontic level; quite possibly a delusion, I realise, but one I doubt I’ll ever be entirely cured of). Explore I must and explore I will. And my explorations have a habit of falling out of my mouth onto pages. (Yes, like a toddler, I often put my mouth where my metaphysics is—and drool. It’s not sanitary or socially acceptable, but there’s no other sensation like it for teething on the real.)

And, of course, I end up just hanging out with those crows, sharing smokes, cracking seeds and cracking jokes, trying not to catch fire, subsisting as best I can.

I should add that I need not call myself a philosopher. I have no pride or preference for the term. As I will discuss in another chapter, in my experience ‘philosopher’ confers little to no status (or sometimes a disapprobatory one). Perhaps there is an equivalent to the Reader I feel myself to be more than literary critic. My dad liked to call himself a ‘theolog’ rather than a theologian. A lay enthusiast, a passionate amateur (a notion of which Chesterton would approve). Yet I think I’m doing significant work of some sort in the same field as philosophers. I am perhaps some kind of scarecrow-clown, generally ineffectual at keeping off the crows. So much so they become part of his sideshow, a murder-murmuration forming shapes above him that illustrate obliquely his carnival speculations. One must picture a scarecrow-clown that can become pensive, melancholy, passionate, as well as playful and foolish, sometimes manically so. The image is patchwork and motley as I am not first and foremost trying to write a biography or memoir but to achieve some para-systemic flickering of the real through a magic lantern of narrative and imagery. If I consider myself a scarecrow-jester, it is because people have worked so long and so hard in these fields before me and I do not presume to supplant them with my casper-come-lately straw-person chaff-chatter; indeed, I defer to them. It is the crows I try to scare away from thwarting the fruit of others’ labour. And, of course, I end up just hanging out with those crows, sharing smokes, cracking seeds and cracking jokes, trying not to catch fire, subsisting as best I can. But here I am, I am what I am, and each plays their part.

As I mentioned at the outset, I write this first and foremost as a way to try to understand myself, with curiosity as to whether a few others might find it helpful in retracing their own intellectual paths. At any rate, it is a very long process and I have begun it self-consciously only late in life (though I continue to find its adumbrations in my earlier years). Perhaps I will have an original philosophical statement or two that I can stand by at the (not too distant) end of my life. (Or a philosophical prank, impression, or prestidigitation. Some metaphysical mugging at the very least?) Meanwhile, I re-cognise myself in the double mirrors. And I set about the task.

To the redoubtable few who made it this far, I say warmly: thank you for reading.

More reports to follow.

solidarity, comrade.

two things keep me from adopting the mantle for myself: one is the compulsory academic distancing that "philosophy" implies. it doesn't always invite people to reach over the velvet ropes and handle the artifacts. i've taken to using the term "applied metaphysics" and "metaphysician" for the more participatory (magical, prayerful, entangled) modalities.

the second is the realization that 99% of Western philosophy—despite its advertised claims—is *not* actually laying down the tracks for some brilliant, progressive, utopian future; rather, when it's functioning well, it's attempting to unfuck some of the catastrophic cognitive mistakes we made by erasing ""animism"" as a form of normative consciousness.

it's like an ontological Houdini act, in which we've chained ourselves in a straitjacket and dumped ourselves into the harbor, and are now furiously struggling to free ourselves before we drown. vitally important effort in terms of survival—but nothing to be celebrated as either practical or heroic, from the perspective of indigenous philosophers who have known better all along.

that's me though. the work itself is still vitally important. and, like you, i can't keep away from it, no matter how i describe what i do. always nice to find a kindred spirit.

Thank you for writing. Very interesting story. Whitehead was of course in a situation not entirely different from yours, taking up philosophy late in life, infiltrating it from the outside. I have also been planning such an academic infiltration at some point so this story was inspiring in that regard.

Deleuze was also very much engaged with this scarecrow work. Thats why he wrote so many books about old philosophers. However, as I see it, such work is ipso facto creative, and Deleuze shows this beatifully. Carnival speculations are the best kind, as Bakhtin knew.